David Enright attempts to figure out the perfect model for justice

Stepping onto a single engine aeroplane from Kathmandu to Pokhara in Nepal, my legal partner, Martin Howe, and I decided to divert our attention away from the frightening prospect of the flight over the Himalayan mountains by continuing our discussion over the meaning of justice and seeking to create an equation to define justice; or more precisely a universal mathematical formula that would deliver it.

Gurkha campaign

We were the lawyers behind what had become known as the “Gurkha Justice Campaign”, which Joanna Lumley later became the public figure head of. For the past two years we had been working with Gurkha veteran soldiers, who wanted the right to settle in the UK after retiring from the British Army following 15–25 years of loyal service.

On this occasion we were en route to the village of Victoria Cross winner, Tul Bahadur Pun. He had won his VC in Burma on 23 June 1943 when, as the last man left standing, he had charged and overcome a series of Japanese machine gun nests that had wiped out the rest of his platoon. His Bren gun jammed almost immediately, and faced with grenades, rifles and machine guns, he had drawn his Kukhri knife and gone from trench to trench dispatching the Japanese machine gun teams. One of those whose life he saved that day happened to be one Major Jimmy Lumley, Joanna’s father.

All fired up

It was stories like his, which were all too common, that had fired us to campaign and litigate for justice for these veterans, the bravest of the brave. But what was justice and how could it be delivered in this case? This issue preoccupied our discussions deep into the hot Nepali nights. It was not long before our arguments ranged wider to explore justice in other cases and contexts; and, in particular, whether there was such a thing as a universal concept of justice.

Justice is the most nebulous and elusive of concepts. Every community, country and age has struggled to define justice and how to achieve it. Like a perfect sunset, we know it when we see it, but may struggle to describe it. It may not be possible to define what a perfect sunset is, but like justice, we can define the essential factors that are most likely to deliver it.

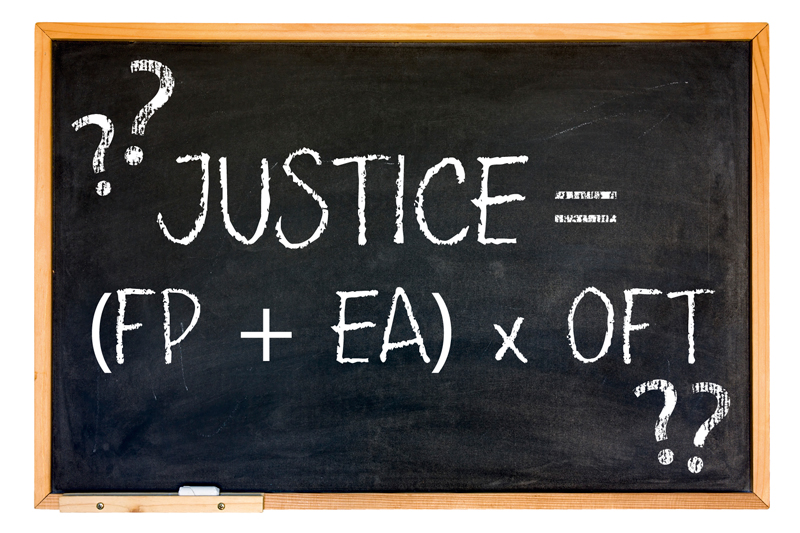

I believe that knowing what justice looks like will aid the vital search for it. As our aeroplane touched down in the eastern Nepali town of Pokhara, we concluded that the universal definition of the perfect model of justice looked like this:

J = (FP + EA) x OFT

J = Justice

FP = Fair process

EA = Equality of arms

OFT = Objectively fair trial

A perfect model?

Although each of the elements of the proposed equation represent complex and contentious issues; students of law will recognise that this equation encapsulates, at a glance, a simple expression of a perfect model of delivering justice.

The elements of the equation (fair process, equality of arms and objectively fair tribunal) have been well rehearsed in the courts of England and Wales and are well understood. However, the equation could just as easily apply in a traditional Land Court of the Maoris of New Zealand or the House of Chiefs in Ghana.

Whether justice is sought in the Supreme Court of the United States, the Royal Courts of Justice in London, or in a Sharia Court in Iran; where a perfect model of justice is found it will look like this.

I would very much welcome comments and criticism.

David Enright JP, Howe & Co Solicitors

E-mail: d.enright@howe.co.uk

.tmb-mov69x69.jpg?sfvrsn=16d9dd3d_1)